Source: Supra-Gingival Minimally Invasive Dentistry: A Healthier Approach to Esthetic Restorations, published by Wiley-Blackwell

Traditional GV Black-inspired preparation rules do not apply to direct composite techniques. These include

- Extensions for prevention

- No enamel without dentin support

- Geometric shape preparations

- Creating gingival clearance by dropping the box

To facilitate the development of more appropriate preparations for direct bonded composite restorations, understanding both the requirements and characteristics of bonded composite is crucial.

The five universal rules for bonded composite preparations are:

- No specific outline, minimally invasive.

- Caries removal should be performed using the most minimally invasive techniques available (the first supragingival principle).

- No boxes or any unnecessary mechanical retention

- No need for unnecessary clearance.

- Beveling.

Rule 1: No Specific Outline, Minimally Invasive.

External or internal GV Black-inspired preparations serve to create geometric shapes that allow for

- The proper thickness of restorative material

- Sufficient access to the cavity for instruments (condensers)

- Mechanical retentive features needed (amalgams preparations)

Outlines are unnecessary with direct composite because composite does not require a certain bulk for strength, condensation by instrument, or mechanical retentive features.

The primary goal of direct composite preparations is the removal of caries and old damaged restorations in the most minimally invasive form, and to allow for the matrix band’s simple placement.

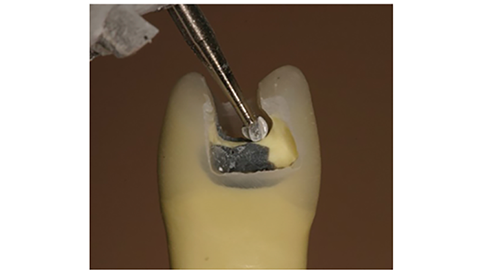

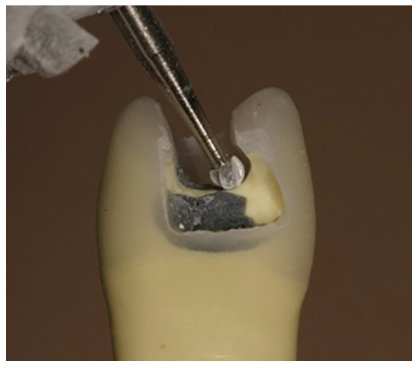

It is acceptable for the access cavity in the proximal caries to be smaller than the internal cavity. An irregular shape is also acceptable (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Class III preparation showing an internal outline larger than the external outline.

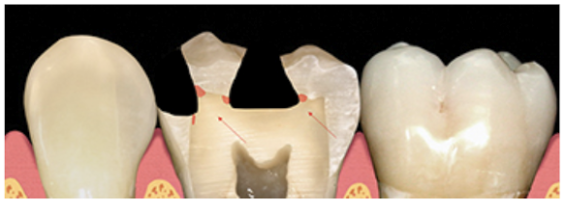

The traditional need for bases to create a flat pulpal floor or form geometric shapes is unnecessary. Additionally, slightly undermined cusps can be preserved and the tooth structure will be reinforced by bonded composite (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Thanks to the reinforcement effect of adhesion, cusps with an undercut and some unsupported enamel can be restored close to their original strength.

Rule 2: Caries Removal Should Be Performed Using the Most Minimally Invasive Techniques Available.

The second supragingival principle shows that when caries removal comes close to the gingiva, extreme attention should be paid during the removal of caries and old restorative material. Clearly infected enamel and dentin must be eliminated from the tooth.

As it may be too destructive, the traditional approaches based on the color, hardness, and the effort to remove all discolored dentin should be questioned. It also may lead to a higher number of pulp exposures or subgingival margins [1].

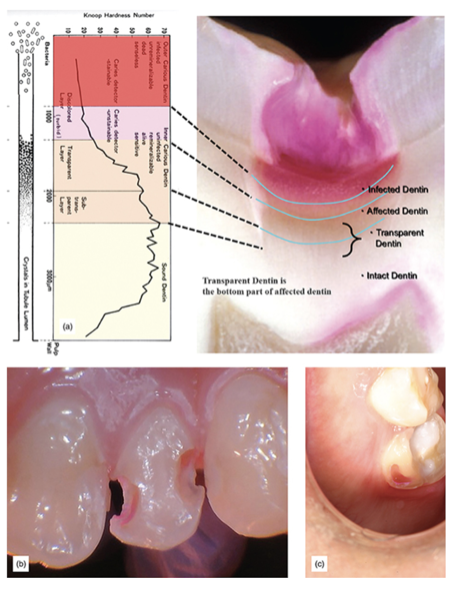

Discolored dentin should not always be fully removed. This is due to it being well demonstrated that dentin caries have two layers [2]:

- The infected superficial layer which is not remineralizable and necrotic.

- The deeper layer affected and stained but not infected. It is also is remineralizable and vital.

Understanding this, preserving the stained but uninfected dentin can be a tooth and pulp saving procedure. Thorough and appropriate removal of caries is crucial, and the use of caries indicators has been demonstrated to be a great addition to catching hidden caries (Figure 3). Caries stains are also a method of detecting the two layers of carious dentin. This was first described by Fusayama, followed by Nakajima [3].

Propylene glycol-based caries stains are used often. The outer infected carious dentin will be stained a dark red and removed. The inner affected dentin will be stained a very light pink, often referred to as a “pink haze” (Figure 4).

The concept of the peripheral seal is important. Special attention should be given to ensuring healthy bondable enamel or dentin at the restorative margins, as well as around the pulp [4]. Since it will remineralize, the inner affected dentin is not removed. Although not as strongly as normal dentin, affected dentin is bondable. Research has also shown that caries-affected dentin will remineralize [5,6].

Figure 3: Areas where caries stain can uncover hidden caries.

Figure 4: (a) Caries layers showing how they stain with a red caries detector (courtesy of Dr. Shigehisa Inokoshi). (b) Red-stained dentin is carious and must be removed. Pink staining shows a non-infected tooth, which should be left, anterior. (c) Caries indicator used to uncover caries on a posterior tooth.

Using a base near the pulp is controversial. The application of a self-etch bonding system directly onto deep or very deep dentin after cavity disinfection or using a self-etch bonding system with strong disinfectant characteristics is a treatment of choice and will provide excellent results [7].

Both the literature and clinical experience show that enamel margins are preferable. They also tend to last longer [8]. Additionally, it is more difficult to place a matrix band and wedge when the margin goes considerably subgingival. Due to this, the care taken during caries removal should also be applied during removal of caries on the cervical margin.

To avoid subgingival margins, the second and third supragingival principles (no boxes or unnecessary retention and enamel preservation and reinforcement) must be taken into account, and enamel preservation techniques should be used [9].

Rule 3: No Boxes Or Any Unnecessary Mechanical Retention

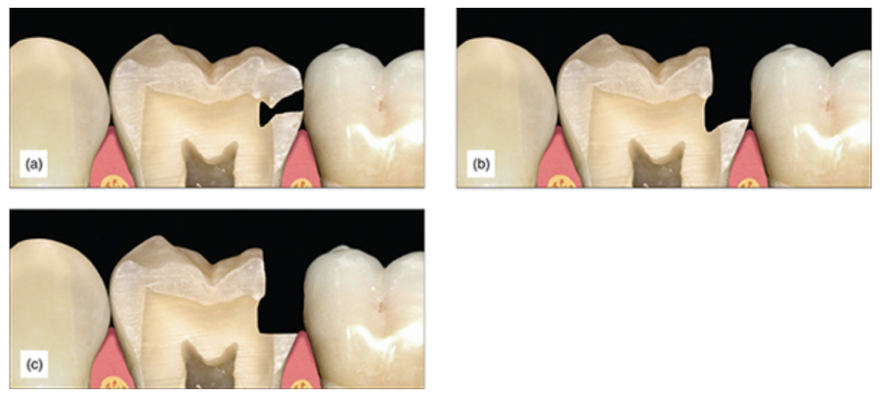

It is counterproductive to intentionally cut mechanical retentive features after caries. It leads to the unnecessary removal of the teeth, increased proximity to the pulp, and subgingival margins. Traditional proximal boxes and dropping the gingival box for clearance is also extremely undesirable.

Interestingly, the difference between stopping after caries removal and continuing to drop the box is usually only one to two millimeters. Nevertheless, that is all that prevents pulp exposure and subgingival margins (Figure 5).

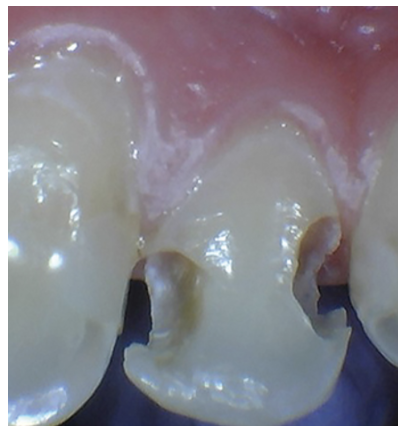

Figure 5: (a) Interproximal caries. (b) After caries removal, the margin is in contact and supragingival. (c) After traditional cervical contact breaking, the margin ends subgingivally.

Rule 4: No Need For Unnecessary Clearance

With older, less flowable materials like amalgam, which required strong packing to seal margins, mesial, distal and gingival clearances were required. Margin visibility was also needed for margin seal confirmation (Figure 7). Bonding systems and flowable composite can also be used to seal margins reliably.

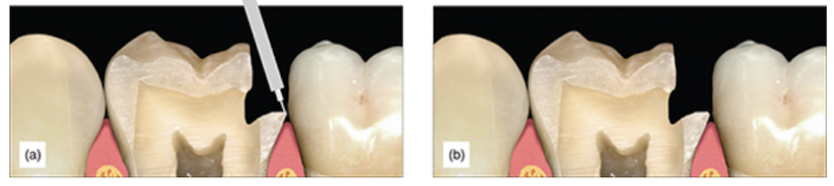

Large clearances are unnecessary. The second supragingival principle suggests creating clearance by using more conservative means, such as metal strips or a mosquito bur (Figure 6). This is necessary for placing of the matrix band. However, only a slight separation is needed.

Alternatively, wedging can facilitate matrix placing. The use of a matrix retaining ring will cause tooth separation sufficient to compensate for the thickness of a matrix band.

Figure 6: (a,b) The finished preparation with minor beveling.

Rule 5: Beveling

Research shows that more rods are exposed when enamel is cut at an angle of 45 degrees. This results in enhanced adhesion. Some studies suggest that this enhances the marginal seal [10], while others suggest minor benefits and that etching enamel can be a sufficient preparation without beveling [11,12]. Others suggest convoluted beveling techniques that require special instrumentation. A meta-analysis has shown that to achieve excellent adhesion, a roughened surface seems to be sufficient. It has also shown that the adhesive system seems to have a large influence on the lack of cervical leakage [13].

Clinically, creating a perfectly even bevel is impractical. The few megapascals gained do not outweigh the extra time spent creating such a bevel. It is sufficient and more practical to simply remove the sharp external cavosurface margin. To complete this step, all that is necessary is to briefly pass a diamond along the cavosurface margin, just to purge any uneven enamel. No specific bevel or thickness of bevel is necessary.

The exception for when longer bevels are needed, is when esthetic blending of the composite with the tooth is desired. For example, class III and VI with facial surface involvement. A 2-3 mm, 45-degree bevel on the enamel will accomplish satisfactory blending when using a composite with appropriate translucency.

We hope this article was valuable to you. Our mission is to provide proven, real-world practical techniques, resources, articles and videos to help the community of caring dentists, who value the benefits of minimally invasive Supra-gingival dentistry, expand their knowledge and achieve clinical success, thus giving their patients a healthier form of dentistry.

For updates on newly published articles, courses, and more, sign up to the Ruiz Dental Seminars newsletter.

Los Angeles Institute of Clinical Dentistry & Ruiz Dental Seminars Inc. uses reasonable care in selecting and providing content that is both useful and accurate. Ruiz Dental Seminars is not responsible for any damages or other liabilities (including attorney’s fees) resulting or claimed to result in whole or in part, from actual or alleged problems arising out of the use of this presentation. The techniques, procedures and theories on this presentation are intended to be suggestions only. Any dental professional viewing this presentation must make his or her own decisions about specific treatment for patients.

Sources

- Heymann H, Swift E, Ritter A. Fundamentals of tooth preservation and pulp protection. In Sturdevant’s Art and Science of Operative Dentistry, 6th ed. Mosby, 2013, pp. 141–163.

- Fusayama T. Two layers of carious dentin; diagnosis and treatment. Oper Dent, 1979; 4(2): 63–70.

- Hosoda H, Fusayama T. A tooth substance saving restorative technique. Int Dent J, 1984; 34(1): 1–12.

- Alleman DS, Magne P. A systematic approach to deep caries removal end points: The peripheral seal concept in adhesive dentistry. Quintessence Int, 2012; 43(3): 197–208.

- Akimoto N, Yokoyama G, Ohmori K, Suzuki S, Kohno A, Cox CF. Remineralization across the resin-dentin interface: In vivo evaluation with nanoindentation measurements, EDS, and SEM. Quintessence Int, 2001; 32(7): 561–570.

- Nakajima M, Ogata M, Okuda M, Tagami J, Sano H, Pashley D. Bonding to caries-affected dentin using self-etching primers. Am J Dent, 1999; 12(6): 309–314.

- Akimoto Momoi Y, Kohno A, Suzuki S, Otsuki M, Suzuki S, Cox CF. Biocompatibility of Clearfil Liner Bond 2 and Clearfil AP-X system on nonexposed and exposed primate teeth. Quintessence Int, 1998; 29(3): 177–188.

- Van Meerbeek B, De Munck J, Yopshida Y, Inoue S, Vargas M, Vijay P, Van Landuyt K, Lambrechts P, Vanherle G. Buonocore Memorial Lecture. Adhesion to enamel and dentin: Current status and future challenges. Oper Dent, 2003; 28(3): 215–235.

- Ruiz JL, Finger WJ. Enamel margin preservation and repair technique. J Dent Res, 2016; 95(Spec Iss 5): Abstract 2370749.

- Swanson TK, Feigal RJ, Tantbirojn D, Hodges JS. Effect of adhesive systems and bevel on enamel margin integrity in primary and permanent teeth. Pediatr Dent, 2008; 30(2): 134–140.

- Isenberg BP, Leinfelder KF. Efficacy of beveling posterior composite resin preparations. J Esthet Dent, 1990; 2(3): 70–73.

- Perdigão J, Anauate-Netto C, Carmo AR, Lewgoy HR, Cordeiro HJ, Dutra-Corrêa M, Castilhos N, Amore R. Influence of acid etching and enamel beveling on the 6-month clinical performance of a self-etch dentin adhesive. Compend Contin Educ Dent, 2004; 25(1): 33–47.

- Heintze SD, Ruffieux C, Rousson V. Clinical performance of cervical restorations: A meta-analysis. Dent Mater, 2010; 26(10): 993–1000.